Norway’s own link to Lady Liberty

Many Norwegians are still claiming their own link to the legendary monument in New York’s harbour. Not only have hundreds of thousands of Norwegian immigrants sailed by the statue, and been part of the huddled masses processed through nearby Ellis Island, the statue itself is believed to be constructed from Norwegian raw materials.

So strong is the claim that the copper for the statue came from a mine in Norway, not least by the Olavsrosa Foundation Norwegian Heritage (external link), that there’s actually a replica of the statue in the west-coast community where the mine is located.

Visnes is a village in Karmøy municipality in Rogaland county, Norway. The village is located on the western shore of the island of Karmøy, about 2.5 kilometres (1.6 mi) west of the village of Avaldsnes. The 0.57-square-kilometre (140-acre) village has a population (2014) of 569, giving the village a population density of 998 inhabitants per square kilometre (2,580/sq mi).

Visnes has a local copper mine that provided material for the Statue of Liberty in New York City. The copper at this site was first discovered in 1865. Visnes was the site of one of the most active of the Norwegian copper mines in history. During the 1870s, it was the largest copper mine in Norway. Up to 70% of Norway’s copper export came from Visnes, which at that time was one of northern Europe’s largest mines. This mine was in full operation throughout much of the latter half of the 19th century and was not fully closed until 1972. The copper mine has its own museum, Visnes Gruvemuseum.

The statue at Visnes in Rogaland County, near Haugesund on the island of Karmøy, commemorates not just the real Statue of Liberty but the Vigsnes Mining Field and its vein that provided the copper for the statue. The vein was discovered in 1865 and it was so productive that it reportedly provided around 70 percent of Norway’s copper export in the late 1800s.

The copper mine itself was owned at the time by a French company, Japy Fréres, which donated all the copper used in the Statue of Liberty.

Much of the documentation that the copper actually came from Visnes, however, was destroyed by fire and newspaper Aftenposten reported that a Norwegian filmmaker tried last year to get new documentation. French sources, however, were not cooperative so the actual original copper was hard to trace. School children in Visnes’ first-grade classes have long been taught at least two things: The text to Fader Vår (the Lord’s Prayer) and that copper from their own local mines dressed the Statue of Liberty (often called Frihetsgudinnen in Norwegian).

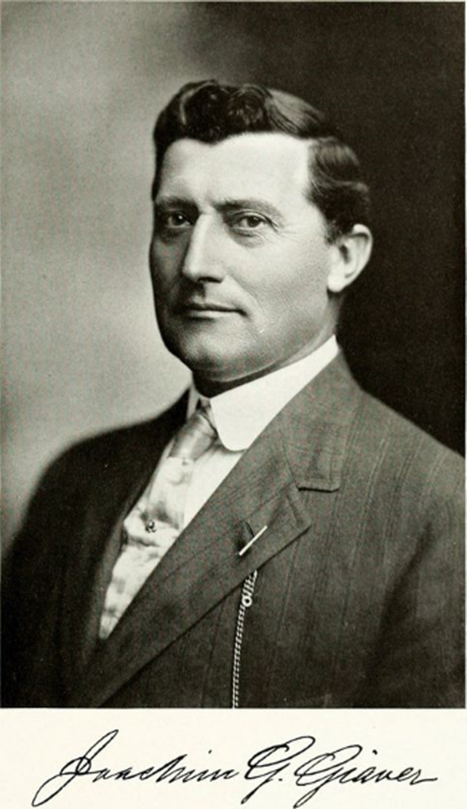

Even without the documentation, there is another Norwegian claim to the statue: Part of its actual construction was overseen by a Norwegian engineer, Joachim Gotsche Giæver, one of the many immigrants to the US.

Joachim Gotsche Giæver (15 August 1856 – 29 May 1925) was a Norwegian born, American civil engineer who designed major structures in the United States.

Joachim Gotsche Giæver was born at the village of Jøvik at Lyngen in Troms, Norway. He was the youngest of eight children born to Jens Holmboe Giæver (1813–1884) and Hanna Birgithe Holmboe (1821–1903). His father was a leader in the local fishing industry. Giæver entered the Norwegian Institute of Technology (Trondhjems Tekniske Læreanstalt) at Trondheim from which he was graduated in 1881 with the degree of Civil Engineer.

He migrated to the United States in 1882, where he found employment as a draftsman at Saint Paul and Pacific Railroad in St. Paul, Minnesota. In 1883, he went to Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, to work as a draftsman and later civil engineer for the Schiffler Bridge & Iron Co. where he designed several bridges over the Allegheny and Monongahela Rivers. He was married in New York during 1883 to Louise C. Schmedling of Trondhjem, Norway.

In 1886, he designed the structural framework for the Statue of Liberty. His work involved design computations, detailed fabrication and construction drawings, as well as oversight of construction. In completing his engineering for the statue’s frame, he worked from drawings and sketches produced by the designer, Gustave Eiffel. In 1891, he went to Chicago to become Assistant Chief Engineer of the World’s Columbian Exposition. In 1898, he became Chief Engineer for the firm of D. H. Burnham & Company, a position he held until 1915.

In 1916, he entered into partnership with Frederick P. Dinkelberg to form the architectural and engineering firm of Giæver and Dinkelberg. Later with the architect firm of Thielbar and Furgard; Giæver and Dinkleberg, he assisted with the design on the 35 East Wacker Building (also known as the Jewellers’ Building) located in downtown Chicago. Designed during 1924 with construction finished during 1926, at the time it was America’s largest building outside of New York City.

He was a trustee of the Norwegian American Hospital in Chicago, President of the Chicago Norske Klub and a member of the American Society of Civil Engineers. He was decorated as a Knight, 1st class of the Order of St. Olav in 1920.